- Home

- Douglas Brode

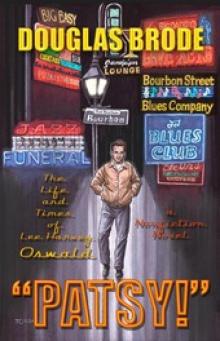

Patsy! : The Life and Times of Lee Harvey Oswald Page 9

Patsy! : The Life and Times of Lee Harvey Oswald Read online

Page 9

Soon the show resumed. Lee would rush away from his window on the world, back to watch, sitting on the edge of the bed he and Marguerite shared each night, glued to the grainy black and white image. At the next advertising break he would return to the window. This became ritualistic, Lee not yet aware of that term. Though Lee could hardly guess it at the time, from that point in his life, his future was forever set in cement.

However addicted to TV he might be, Lee found one show repulsive. The Adventures of Ozzie and Harriet featured members of the Nelson family, mom and dad and two sons, all playing themselves. They lived in a wholesome looking neighborhood, got along great. No one ever raised a voice. Lee smelled a rat.

People weren’t like that. How dare they put on a show that dangled an ideal family in front of the eyes of all those who could barely, and rarely, achieve even a little happiness?

He abruptly turned the channel and never watched it again.

*

On one of their sojourns into the affordable fun places in and around the New York City area, John had offered to buy Lee a souvenir. The boy picked out an inexpensive pocket knife. Sheer horror would result from this seemingly innocuous incident.

Over the past two weeks, Margy had grown frustrated, then furious, with the intensifying realization that Marguerite had arrived with plans for her and Lee to become permanent fixtures. Not that Mama ever said this outright; Marguerite’s manner of dealing with situations was to remain silent and hope, even assume, what she wanted would transform into reality.

Margy set out to do something about that. She began dropping hints that the apartment was too small. Marguerite responded that in time “we’ll get a bigger one.”

We? You were invited for a few days!

Margy complained that Lee ate a lot for a skinny kid, hoping Marguerite would take the hint and offer to find work. “He’s a growing boy,” Mama shrugged. That did it! Margy wandered around her limited space, only days earlier her domain, now clearly her mother in law's, ever more depressed.

One day shortly thereafter, Margy stepped zombie-like into the kitchen area and happened upon Lee, sitting at the table, dutifully employing his new penknife to carve a miniature ship.

“Look!” Margy over-reacted, pointing at a small mess on the floor. “You’re getting wood chips all over everything.”

“I’ll pick ‘em up when I finish,” Lee shrugged, not bothering to look up. He failed to grasp any immediacy to this minor situation. Emitting a sound just short of a banshee’s shriek, Margy slapped the boy across the face. Her open-hand blow landed so hard it sent the child flying across the room.

Shocked at the impact of her swing, already half-wishing she had not done it, Margy nervously stepped over toward Lee, concerned as to his welfare. As she approached, the boy leaped to his feet, bringing the penknife forward in self-defense.

“Do that again,” he screamed, “and I’ll kill you!”

Lee had never spoken in such a way to anyone before. He’d heard it in an old Allan “Rocky” Lane B Western that ran on TV’s The Gabby Hayes Show the previous week. If Rocky said it ...

“That’s it!” Margy hissed, knowing full well that if she hadn’t checked her own forward movement she might well have run into the knife and been killed. “You two are out of here!”

Upon return from work, John tried reasoning with Margy. To no avail. She may have been glad the incident occurred; at last, she had an excuse to send them packing. John assured Lee he’d regularly stop by, wherever Lee and Marguerite settled in the area, continuing to take him to the movies. Lee would have none of it. So far as he was concerned, John had betrayed the family by siding with Margy. Lee never spoke to John again.

Not even when John and Margy were invited over to the new apartment Marguerite had located in the Bronx, just off the Concourse, for Sunday supper a month and a half later. Robert, on leave, had come up to visit. The moment Robert appeared in their doorway, wearing his marine dress uniform and beaming proudly, Lee knew this was what he hoped to one day become.

*

"So you respect your big brother’s choice?” the marine recruitment sergeant asked after Lee described that reunion.

“You can’t imagine. So very much!”

“My great concern, Lee, is that you have a dangerously romanticized view of what the Corps will be like—”

“If I may interrupt?” Lee leaned forward, anxiously.

“That’ll be fine.”

“Actually,” Lee continued, “I know everything about the marines. Your history, the code of conduct—”

“My turn to interrupt. Where did you pick this up?”

Lee explained the circumstances of Robert’s visit, leaving out as much of the personal stuff—those bad feelings between himself and John and Margy, Marguerite's over-the-top act for everyone, as if all their world were a stage, she the designated lead player—as he dared. There had been a family Sunday supper, quite elaborate in light of Marguerite’s modest means.

All five, the Oswalds and the Pics, seated together at her dinner table in a mutually understood state of truce. Marguerite wore her finest dress left over from those brief upscale Fort Worth days. Everyone might have relaxed, even grown comfortable, if she hadn’t gone into her infamous Southern Belle routine.

"Mom,” John made the mistake of saying, “would you please just be yourself and stop putting on airs?”

In a grand gesture, Marguerite fell with a theatrical faint into a nearby stuffed chair, then began bawling. “I’m sorry if I try to add a touch of quality to my surroundings, humble as they may be.” Tears rolled down her aging cheeks.

Robert tossed John an angry look for spoiling everything, though he’d been thinking the same himself. She reminded him of Vivien Leigh as Blanche du Bois in the movie A Streetcar Named Desire. He’d joined the corps mainly to get far away from Mama.

Two years earlier, John had enlisted in the Guard for the same reason. The two often talked about their difficult home situation at night, when neither could get to sleep, at the orphanage. Even as other boys might fantasize about a life of adventure, they shared their desperate dreams for normalcy.

“I’m going out,” Lee announced. No one said a word as he pushed his half-finished plate away, rose without making eye contact with anyone. He slipped on his jacket and left.

“Where will he go?” Robert worried.

“My guess is to the Bronx Zoo,” John shrugged. He and Marguerite, speaking alternately with Margy throwing in side comments, related Lee’s problems. Shortly after the current school year commenced he began attending P.S. # 117. Other boys picked on him. Some gave Lee a hard time owing to his outdated clothing. Others viciously mocked his modest southern accent. All sensed something irregular—”queer,” a few ventured—about this new kid. The girls picked up on that and avoided him.

Sickened at the thought of enduring such humiliation, Lee would each morning wait for Marguerite to leave, he pretending to be on his way as well. Once she was gone he’d stay home. All morning Lee watched TV. At noon, he would take a break, make himself a sandwich, meanwhile turning on the radio. That’s where his appreciation for Sinatra began. In early afternoon Lee would shove off, most days heading back to the zoo via the subway.

When the principal realized this new boy had attended only fifteen of the first forty-five school days, he sent a truant officer out looking for Lee. The man found him at the zoo, exchanging smirks with the monkeys. He grabbed Lee by his ear, twisting it cruelly. This immense bully then dragged the pained, humiliated kid back with him.

Lee tried to suffer through school, actually enjoying social studies and English literature classes, if miserable again when the bell rang. For the three minutes allotted to changing class-rooms, he felt alienated from all others in the crowded corridor, sometimes harassed by bigger boys.

Soon Lee headed back to the monkey cage.

*

The truant officer, figuring where he'd find him, came by. After th

at, Lee spent afternoons riding the subway, across and under the great city above. He made it a point to learn every stop and the precise distances between them. Lee appreciated such minutiae; a sense of power flowed through him knowing that he possessed myriad details that other people lacked.

I’m invisible to them. Someday, they'll see me ...

Lee most enjoyed those rare occasions when he had a car all to himself. Then it was as if the entire New York subway system operated for that brief interlude for Lee alone. When a car grew crowded, sometimes Lee would get off, go up, tenuously exploring the real world. Most areas were too crowded with Normals for Lee to feel comfortable.

One place he did appreciate was Greenwich Village. Lee loved the huge arch, done in an ancient style, at the entrance to a park where the Beats congregated, strumming their guitars, spouting incomprehensible poetry.

“The times, they are a-changin’,” one bearded boy, no older than Lee, warbled mournfully.

Mostly Lee was fascinated by the chess players, a unique breed of societal drop-outs. They sat on benches, challenging passersby to pay for a chance to match their skills. Whenever he had a little extra money, Lee would give it a try.

He came to know some of these fascinating characters, wondering if this might provide a possible career. Though Lee never beat any of them, on more than one occasion he came close. An elderly black man, whom Lee believed possessed all the wisdom in the world, winked and assured Lee he was good. Damn good!

Black people appreciate me in a way whites don’t. As to chess, I’ll bide my time, practice, and maybe someday ...

At a book stall, Lee picked up a home-printed pamphlet that had a major impact on his vision of self. Called “The White Negro,” the piece had been authored by Norman Mailer, a scribe whose WWII novel The Quick and the Dead had elevated him to the level of celebrity author. The seller explained to Lee that this brochure had been produced by something he referred to as The Underground Press, an indie publisher called ’City Lights.’ Lee hadn’t heard that term before. He wanted to learn more soon.

Naively, Lee expected this to be about black people born with paler-than-expected skin. Instead, Mailer wrote about Anglos who had fallen in love with black culture, everything from jazz sounds to interracial romances. These were the Beats Lee had heard about, both here in The Village and haunts in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury. Hipsters, Mailer called them.

Subterraneans, not suburbanites. They played bongo drums, danced the night away, and rejected contemporary Christian conformity to celebrate dark and ancient gods. They believed in free love and free thought, freedom for the body and the mind.

Could Mailer be talking directly to me, showing me the way?

One point that mesmerized Lee was Mailer’s distinction between the psychotic and the psychopath. The former would be identified by society as a menace and incarcerated. The latter could pass unnoticed, a face in the crowd, until some day he, without warning, exploded with violence.

That second type of person ... that may just be me.

Lee spent an hour reading the piece on a bench. On future visits he would purchase the novels of Jack Kerouac and poems by Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Allen Ginsberg. “Coney Island of the Mind.” “Howl.” A whole new world opened up to Lee.

This continued until Lee was picked up again, now by a different truancy officer, nastier even than the first. Lee was summoned to appear in Children’s Court, Marguerite required to take an afternoon off work to accompany him.

“I have no authority over the boy,” she wailed to the judge. “I make him promise to attend school, but he runs off anyway. I have to work. What am I to do?”

“Madame,” the judge snapped back, “if you cannot control your child, I will deliver him to those who can.”

*

Shortly after turning thirteen, Lee was bundled off to Youth House, a horrible refuge for abused and/or disoriented children. Lee guessed the place was worse than any environment these kids may have come from. The other boys, all misfits too, taunted and bullied Lee. He withdrew to any private place he found, reading. Dickens; Little Dorrit. Sharing the suffering of others helped Lee survive. At least he wasn’t alone.

He loved escapism as much as realism, so Lee grew ecstatic when he saw a volume called Invisible Man in the library. He’d caught the old Universal horror movie on TV a few years earlier and looked forward to H.G. Wells’ original. To Lee’s surprise, this turned out to be a new novel. Not ‘The’ Invisible Man but simply Invisible Man, by Ralph Ellison. From page one L.H.O. realized this was penned by a man of color. The title did not indicate science-fiction but social status.

“I am invisible,” Ellison stated, “simply because people refuse to see me.” That, Lee could sympathize with. As he walked the crowded streets, people passing by made eye contact with every other stranger except him. He could almost believe there existed a confederacy of silence to avoid and isolate L.H.O. He and of course all the black people in America as well.

During Lee’s term of residency, a psychiatrist named Carro observed the boy on several occasions. He alone among the staff doctors was able to persuade this particular boy to open up and talk. Lee’s chaotic behavior, Carro insisted, stemmed directly from a sense of impermanence as to any place he might inhabit, any status he temporarily possessed; always believing if these were decent, they’d soon be taken away. If not, things could only get worse. Frequent moves in class and place had long since fractured any sense of personal identity, perhaps beyond repair.

“In my mind,” Carro wrote in his official report, “there developed over time an inability to adapt to the changes ... Normally, a person meets these kinds of situations. Either you face them head on or you retreat. Perhaps Lee did the former for a while, trying his best to make do with an ever shifting reality. But the frequency, and drastic alterations as to lifestyle, may have proven too much for him to handle.”

As a result, Carro came to believe Lee had without being aware of the process created an invisible shield around himself; a protective cocoon which the world, however oppressive, could not penetrate. Inside that invented, imaginary safe place, Lee designed and inhabited an alternative reality, one in which he existed as an all-powerful being. Different became superior.

Lee “feels as if there is a veil between himself and other people through which they can’t reach him,” Carro stated. If at some time in the recent past Lee had hoped to join, he “feels as if there now exists a veil between him and other people through which they can’t reach him.” Carro concluded that, if previously Lee had even remotely wanted to rejoin the brotherhood of man, The Normals, any such desire might be gone and forgotten. Now, Lee Harvey Oswald “prefers this veil to remain intact.”

Robert, who had no idea of how terrible things had become, gasped. What had an uncaring world done to his kid brother?

“I only wish I could help,” John explained, “but he’ll have nothing to do with me since ’the incident.’”

“If you like,” Robert suggested, “I’ll try to get him to open up to me as soon as he returns.”

“That,” Marguerite announced, “would be wonderful!”

*

“I was a little mixed up a few years ago.”

“Most kids are at that age,” the sergeant responded.

“Robert said to me, ‘Look, Lee, you can surrender to chaos or you can learn discipline. If you do the former you may have a wild ride for a while but you’ll end up lost and alone. If you opt for the latter, you’ll earn yourself a satisfying life.”

“Your brother sounds like a very smart man.”

“Of course he is,” Lee gulped. “Like you, he’s a marine.”

The sergeant smiled back. For the first time, the recruiter actually believed that this kid might just have a shot.

“You want to know what Robert said the last time I saw him?” Lee—realizing he was winning the marine over—asked in a rhetorical manner. “Boy, if you ever get into the marines, you are

going to end up a general!”

During the next half-hour, Lee continued his story about Robert’s visit. How he read over the marine manual with his brother. When Robert left, he allowed Lee to keep the book. The boy read it over and over until he had it memorized. To prove himself, Lee ran through a litany of details—care of the M1 rifle, the philosophy of martial arts, the esprit de corps necessary for absolute commitment—stunning the sergeant as to Lee’s veracity, comprehension, and passion for the Marines.

Lee didn’t mention some of his other reading matter for fear the sergeant would send him packing. During one of Lee’s visits to The Village a stumble-bum struck up a conversation about communism, insisting it would replace our own capitalist system, and there was nothing anyone could do to stop that. Lee had conversed with the elderly fellow calmly for a while, then began ranting about the true greatness of democracy.

About a week later, as Lee ascended from a subway stop, he came face to face on the street with a dreary woman, handing out pamphlets about the immorality of the Rosenbergs having been convicted and executed as spies on flimsy evidence that they’d sent atomic bomb secrets to Russia. Initially, Lee brushed past her; then, something snapped. He turned, headed back, took one.

At the apartment, where he lived alone now since Marguerite had disappeared again—she would return sooner or later, acting as if this were completely normal—Lee read it with interest.

As it happened, WOR-TV in New York, Channel 9, re-ran on weekdays a half-hour filmed series called I Led Three Lives. The show had been based on a bestseller by Herbert J. Philbrick. This advertising executive balanced his home life as an average white-collar worker and devoted husband with secret activities as a member of a clandestine Commie cell planning to overthrow our government. Perceived as a traitor by neighbors who learned of his double identity, Philbrick kept a greater secret, one he would not share even with his distraught wife: he happened to be a special agent working for J. Edgar Hoover. A patriot, Philbrick was willing to go down in history, if need be, as the worst traitor since Benedict Arnold in order to serve his country.

Patsy! : The Life and Times of Lee Harvey Oswald

Patsy! : The Life and Times of Lee Harvey Oswald